Chronic stress can differentially change the neuronal structure and function in the brain, leading to anxiety disorders and other neuropsychiatric illness. Now, researchers may understand how the different change occurs.

The team from Nanchang University published their findings on November 30 in Stress and Brain.

“Prolonged stress alters the structure and function of only some neurons in the amygdala, a brain region essential for emotional regulation and a critical mediator of stress response and fear learning,” said corresponding author Jun-Yu Zhang, associate research fellow in the Laboratory of Fear and Anxiety Disorders in Nanchang University’s Institute of Life Science. “In this study, we attempted to find the possible mechanism of the differential regulation by prolonged stress.”

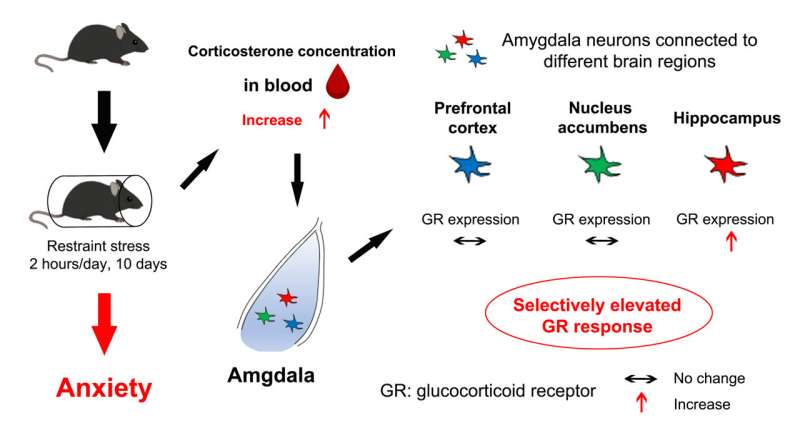

Neurons in the amygdala connect to other areas of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex—involved in cognitive control, the nucleus accumbens—helps translate motivation to action, and the hippocampus—which plays a significant role in memory and learning. In previous research, Zhang and her team found that the neurons connected to the hippocampus were drastically altered under chronic stress, while those linked to the prefrontal cortex and the nucleus accumbens remained unchanged.

“These neurons integrated in different neural circuits are in almost the same microenvironment, but triggered different reactions to stress, suggesting that the remodeling shows obvious circuit selectivity in the process of chronic stressed-induced excessive anxiety, but the regulatory mechanism has remained unclear,” Zhang said.

“Considering the critical role of glucocorticoids—a stress hormone—in the modulation of brain structure and function by stress, we hypothesized that the glucocorticoid receptor may be a potential mediator of the differential regulation of neurons by chronic stress.”

To test this hypothesis, the researchers exposed four groups of mice to various durations of restraint stress. Over 10 days, the mice were put into a tube fitted to their bodies for either two hours one time, two hours on three days, two hours every day or not at all. The researchers examined how the levels of corticosterone (glucocorticoid in mice) and the expression of the glucocorticoid receptors changed throughout.

They found that the levels of stress hormones in the mice increased continuously with restraint time, and they increased remarkably in the mice stressed every day. They also found that the chronic stress did not affect the number of neurons expressing glucocorticoid receptors, but that it did appear to significantly increase the intensity of expression only for neurons projecting into the hippocampus.

“Our results indicate that the increase of stress hormone concentration in mice, caused by prolonged stress, only selectively causes the significantly up-regulated expression and excessive response of the receptor in the amygdala to hippocampus neurons, suggesting that this signaling pathway may play an essential role in the differential regulation of neurons in the amygdala,” Zhang said.

“This study advances our understanding of the effects of chronic stress on the functional circuit of the amygdala, but the specific mechanisms of how the receptor mediates the differential regulation of chronic stress are not yet clear.”

The researchers plan to further study the glucocorticoid receptor mechanism by examining the effects of chronic stress when the receptor is blocked or removed.

Source: Read Full Article