A dizzying array of cardiac imaging tools allows clinicians to visualize the structure and function of the heart better than ever before, making it difficult to keep up with appropriate indications for their use. And it has become common for patients to present to clinic worried about alarms triggered by their smartphones and smartwatches.

Dr Matthew Tattersall

The identification of coronary artery calcium (CAC) testing tops the list of imaging results that can lead to downstream testing and referrals. “We’re seeing a lot of referrals for patients who have incidentally detected calcium on some non-gated chest CT,” said Matthew Tattersall, DO. “One of the things that seemed to be pretty universal with these individuals is that they were quite anxious. They’re scared.”

Tattersall, an associate professor of cardiology at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, is describing a common scenario. Although the National Lipid Association (NLA) recommends use of CAC testing to make decisions about use of statins in patients aged 40-75 years with a 10-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) of 5%–19.9%, or with <5% risk but with a family history of premature ASCVD, patients are showing up in his clinic who had a chest CT performed for another reason.

“We’re seeing a lot of referrals for patients who have incidentally detected calcium on some non-gated chest CT,” said Dr Matthew Tattersall. “They’re scared.”

Instead of undergoing a formal assessment of CAC, which requires ECG gating to capture data during a defined portion of the cardiac cycle (and is rarely covered by insurance), his patients have had a non-cardiac, non-contrast chest CT, or maybe even an abdominal CT. But the radiologist dutifully documents the presence of calcium in the coronary arteries — often triggering a referral or additional screening.

The NLA guidelines do not address the situation of when CAC is detected incidentally, but a recent study evaluated the rate of statin prescriptions in patients without a previous diagnosis of ASCVD whose doctors were notified of the presence of incidental CAC compared with a control group who were not notified of their findings. Patients in the notification group were more likely to receive statin prescriptions than those in the control group, suggesting a potential benefit of using CAC data whenever it’s available.

However, an accompanying editorial pointed out a downside of the intervention: More of the patients in the notification group compared with the control group (15% vs 2%) underwent additional evaluation for ASCVD, mostly stress testing, which was likely unwarranted.

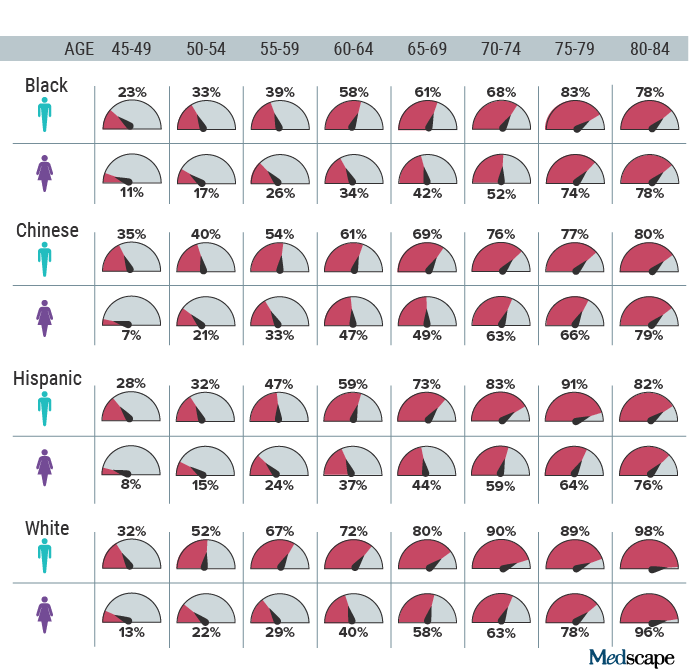

To help clinicians put the presence of CAC in perspective, Tattersall and colleagues recently published a new analysis from a previously published prospective cohort study, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), which provided data on the prevalence of CAC in a group of individuals who were not previously diagnosed with ASCVD.

“We can basically frame the discussion between the patients and the physicians about what the expected prevalence of coronary calcium is based on their age, sex, race, ethnicity,” Tattersall told Medscape Medical News.

The prevalence of a nonzero Agatston coronary artery calcification score rises with age. Adapted from Tattersall et al. JAMA Int Med. Sept. 25, 2023.

For example, the table in their recent research letter shows that 80% of adults over age 80 have detectable CAC, so a patient in that age group who has a low 10-year ASCVD score probably would not benefit from a prescription for statin. But only 17% of Black women aged 50-54 have detectable CAC. For those women, the finding of CAC could lead to a conversation between clinician and patient about whether to start statin therapy.

No Symptoms, No Test?

Friederike Keating, MD, a nuclear cardiologist and professor of medicine at the University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington, often receives referrals for stress tests where the justification is “coronary calcification seen on a chest CT.” She acknowledged that some of the referrals may be justified, but most are not.

“If somebody doesn’t have any symptoms, and they just have calcium in their arteries, they should have a discussion with their doctor,” Keating told Medscape. “But they shouldn’t necessarily be referred to get a stress test if they otherwise don’t have any symptoms.”

Dr Friederike Keating

Keating headed the most recent cardiology workgroup for the Choosing Wisely campaign, an initiative of the American Board of Internal Medicine that sought to generate informed patient physician conversations about unnecessary tests, procedures, and treatments across all internal medicine specialties. For the cardiology recommendations, titled “Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question,” her group tried to prioritize tests and procedures that are commonly ordered but not always needed.

CAC testing in patients already known to have ASCVD — and thus likely already taking a statin medication — made their top five list, along with advice to avoid obtaining routine serial echocardiograms in patients with chronic heart failure who are clinically stable. Another is to avoid routine imagine stress tests or coronary CT angiography for the workup of palpitations or presyncope.

Keating said she hopes reducing superfluous tests will help cut down on unexpected but ultimately meaningless findings: “We don’t like to have too much in the way of incidental findings because you always get down testing rabbit holes, right?”

John Mandrola, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist practicing in Louisville, Kentucky, has long been critical of CAC testing. “There is a theoretical harm of extra radiation,” he said, “But I think the main risks that I worry about are the non–evidence-based downstream testing that comes of this.”

Dr John Mandrola

Mandrola, a frequent contributor to Medscape, has his own list of top three unnecessary tests, and CAC tops the list. For CAC he described two scenarios that lead to superfluous testing: patients who are already taking statins who get sent for CAC testing, and CAC testing to evaluate patients with atypical chest pain who are at low risk for having a myocardial infarction. For these patients, CAC is usually incidental and not related to what is often non-cardiac chest pain.

Next on his list? Too much stress testing. In addition to the Choosing Widely recommendation to avoid stress testing for workup of palpitations or syncope, Mandrola often sees stress tests used to rule out cardiac causes of chest pain in patients at little risk for ASCVD. He pointed out that troponin testing is a much better tool for diagnosing a heart attack

“If someone comes in with very atypical pain, has a low pretest probability of ischemic heart disease, and has negative troponin testing, there’s very little reason to do stress testing,” He said.

Mandrola’s last pet peeve is excessive heart rhythm screening among asymptomatic individuals, particularly in the age of wearable devices. The main issue is that continuous monitoring with mobile devices, either medical devices or a smartwatch, often pick up episodes of atrial fibrillation of short duration that would have gone undetected 10-15 years ago when the standard of care was a single 12-lead EKG. “These cardiac devices can pick up 1 hour or 3 hours of atrial fibrillation, which would probably be best not to know about,” he said.

Why not? Not every patient with AFib needs treatment. Data suggest cardioversion of patients with recent onset (< 36 hours) symptomatic AFib may be safely delayed, and that in some cases patients with brief episodes of atrial arrhythmia resembling AFib may not benefit from oral anticoagulation, and may even carry higher risks of death or major bleeding.

Mandrola likes to quote Voltaire, who famously said, “The art of medicine consists of amusing the patient while nature cures the disease.” For modern clinicians, that might translate into spending more time with patients weighing the risk and benefits of CAC and stress testing before opening Pandora’s box.

Tattersall, Keating, and Mandrola reported no relevant financial relationships.

Ann Thomas, MD, MPH, is a pediatrician and infectious disease epidemiologist living in Portland, Oregon.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn

Source: Read Full Article