In June, India began using cheaper, faster but less accurate tests to scale up testing for the coronavirus—a strategy that the United States is now considering.

These rapid tests boosted India’s testing levels nearly five-fold within two months. But government numbers suggest some parts of the country might have become over reliant on the faster tests, which can miss infections. Experts warn that safely using them requires frequent retesting, something that isn’t always happening.

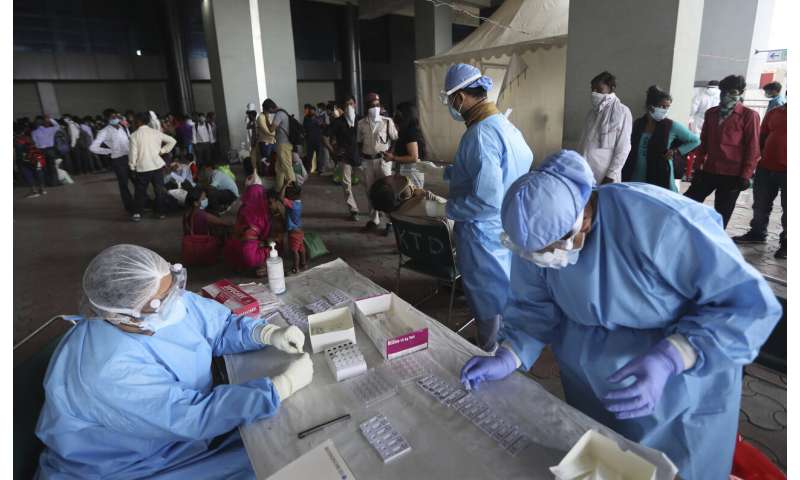

Cases surged faster than labs could scale up testing once India’s harsh lockdown was relaxed. So far authorities have rationed the use of the more precise molecular tests that detect the genetic code of the virus. But on June 14, India decided to bolster these with faster tests that screen for antigens, or viral proteins.

Albeit less accurate, these tests are cheap and yield results in minutes. Most don’t require a lab for processing or any specialized equipment or trained personnel. The plan was to rapidly increase testing to identify infected people and prevent them from spreading the virus. Samples tested using both tests increased from 5.6 million in mid-June to 26 million two months later, and nearly a third of all tests conducted daily are now antigen tests, health officials say.

But India’s experience also highlights the inherent pitfalls of relying too heavily on antigen tests, at the expense of more accurate tests. The danger is that the tests may falsely clear many who are infected with COVID-19, contributing to new spread of the virus in hard-hit areas.

Rapid test results can be backstopped with more accurate laboratory tests, but these are slower and expensive. Experts also warn that since the two types of tests vary in accuracy, they need to be interpreted separately to properly assess the spread of infection—something India isn’t doing.

The U.S. faces a similar need to strike a balance between speed and precision, with overburdened labs struggling to keep pace with the outbreak. Researchers at Harvard and elsewhere are proposing developing a $1 saliva-based antigen test for all Americans to test themselves daily, something that has not yet been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Harvard’s Dr. Michael Mina says antigen tests don’t catch as many patients early in the infection, when virus levels are low. But these people aren’t considered the greatest threat to spreading the disease since it’s only after virus levels surge that they become more infectious, and by then they will be picked up by antigen tests, he said.

Because a negative antigen test doesn’t guarantee a person is virus free, people should be retested regularly, said Dr. Ashish Jha, director of Harvard’s Global Health Institute. “If their symptoms change, you want to think about retesting those people.”

India’s strategy is different. Health officials have asked for those who test negative with antigen tests but have symptoms to be retested with the more accurate laboratory tests.

But India has largely been opaque about how many negatives were being retested, and what type of tests were being used.

Delhi state, which includes the Indian capital, New Delhi, and where the High Court is monitoring testing, was among the first to aggressively use antigen tests to screen patients for free. Centers were created in dispensaries, schools and government offices. But only 0.5%, or 1,365 of over 260,000 people who tested negative from June 18 to July 29, were retested, court documents show. Delhi conducted over 280,000 tests in this period.

“That is abysmally low,” said Dr. S.P. Kalantri, a public health specialist in Maharashtra, India’s worst-hit state. He said the decline in use of more precise lab tests by nearly half, from a capacity of 11,000 tests daily to just 5,400 tests per day, was a worrying trend

Under guidelines set by the World Health Organization, India should be conducting around 140 daily tests per million people in order to safely relax coronavirus restrictions.

Rajesh Bhushan, India’s top health official, has repeatedly pointed to India’s cumulative total of the two types of test to assert that India is testing more than the WHO standard. Authorities also use this to calculate the percentage of samples testing positive, which is a key metric for judging testing performance.

But Jha said combined data from the two types of tests can’t be used to conclude that infections in India are going down, since using less accurate tests would automatically drive down the number of positive results.

Experts fear that over-reliance on antigen tests without retesting could impede efforts to contain the virus as it spreads to states with fragile health care systems, like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, with a combined population of over 300 million.

The two states now conduct over 100,000 tests daily, the most in India. But only a fraction—6,100 in Bihar and 30,000 in Uttar Pradesh—use laboratory tests.

Jha said the antigen tests were a way to expand testing for people who don’t have access to laboratory tests, but that didn’t mean use of the more accurate tests should lessen.

Source: Read Full Article